Eric Alexander

|

21 december 2013

|

|

Jazz Inside Out

|

|

© Jazz Hot n°666, winter 2013-2014

|

Eric Alexander has a complete range of talents: he is a leader, sideman, composer, educator. And above all, he loves to share his passion for jazz. Born in 1968 in Galesburg, in Illinois, the saxophone player has been playing since he emerged in the early 90s with the greatest musicians, from Pat Martino to McCoy Tyner, to Joe Chambers and Hank Jones, without forgetting the musicians of his generation, Vincent Herring, Peter Bernstein, Sam Yahel, to name a few. While studying at William Paterson College, he was taught by Harold Mabern and since then he has kept their friendship and musical bond alive. By his lyricism, elegance and solid playing, Eric Alexander follows in the footsteps of George Coleman and Sonny Stitt while shaping his own sound. His vast discography offers many examples. Besides touring in the USA, Japan and Europe, he coleads One For All, with Steve Davis, Jim Rotondi, David Hazeltine, John Webber and Joe Farnsworth, a band that only plays original compositions. As a leader, he plays with Harold Mabern, John Webber and Joe Farnsworth for intense jazz sessions.

Interview by Mathieu Perez

Discography by Guy Reynard and Yves Sportis

Jazz Hot: How did you get involved with music?

Eric Alexander: Like a lot of children, my parents exposed me to music to a certain degree. My father was a big classical music aficionado and had an appreciation for jazz. My mother wasn’t much of a listener but rather a performer. She would sing in the church and enjoyed playing piano. They weren’t musicians, just amateur enthusiasts. But they both thought that music was important. My mother insisted that I take piano lessons from 6 years old to 11 or 12. One day, I told her that I wanted to quit. My mom said ok. She was tired of telling me to practice. I took up the saxophone later. In high school, I started playing classical saxophone.

At what point did you want to become a professional jazz musician?

Very late! I was at least 19 years old.

What triggered it?

As is true for a lot of young people that are involved with music, they know in their heart that that's what they want to do they are lacking inspirational experiences. They may love Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers but have never heard it. As soon as someone shows it to them, it’s a new world. Music was in me, it was waiting to come out. When I was in college in Indiana, I didn’t major in music but I met musicians and when I heard them play, I told myself that I would never be that good. My next thought was that I had to figure out how to do what they did. And then it was an incredible motivation. People turned me onto great recordings. At that time, I had never heard Joe Henderson! I distinctly remember hearing an album by Sonny Stitt -who became one of my early influences- during my sophomore year of college. It was a revelation for me. It sounded so great! Now in retrospect, when I listen to those things, I don’t hear the same things because I know what they’re doing to a much greater degree. When I listen to a melody by Sonny Stitt, with that kind of perfection, I still can’t believe it!

How much did you practice at that time?

If I wasn’t with the horn in my mouth, I was listening to music. I would be practicing five, six, seven hours a day. That’s not legendary level but I was focused and practiced with the intent to learn. I also would go to concerts and see people play and that was really inspiring. Music was floating around in my mind.

Did you like studying at William Paterson College?

I was 20 years old when I got there. My teachers were Harold Mabern, Joe Lovano, Rufus Reid, Steve Turre, Gary Smulyan, Ralph Lalama, Norman Simmons, among others. The real beautiful thing about William Paterson was that the students had a connection with the musicians that were playing every night in New York City. They were the real cats, really connected to the music.

How long did it take to get to know Harold Mabern? How long did it take to get to know Harold Mabern?

The first second at the first class! In a way, it was pure luck because he has a habit of asking his students to name their favorite players. The first three names that came to my mind were John Coltrane, George Coleman and Sonny Rollins. That was a stroke of genius since he worked with George Coleman. So he liked me right away! Otherwise I don’t know why he liked me since I couldn’t play shit! (laughs) I couldn't play at all! But some teachers, who are very perceptive, can see something…

What was his method for teaching?

He had ensemble groups. He would come in every week with a tune or a musical pattern and have us listen to it and make us play it over and over. Some of the students, like me, loved it. I remember every single tune and pattern he taught me. Others didn’t like it because it’s a different way of processing information. But for me, it was very important because I was always relying on music and he got me to use my ear and my brain, which is what I rely on now. If someone gives me a sheet of music, the first thing I do is to process it in my brain and ear. I try to get away from the music. So for me, this method was fantastic.

What did you learn from him at that time?

He was inspiring on a personal level. He was so excited about jazz music, its heroes and experiences. It makes you uplifted and want to do more. He is my first real musical father and still is. He taught me enthusiasm and awareness.

How long did it take before you and Mabern started to work together? How long did it take before you and Mabern started to work together?

Not long. I always hoped that I would be able to call him at some point. I graduated in June 1990 and by August 1992 I was doing of recording with him [Straight Up, Delmark].

Over the years, how did your relationship with Mabern evolve?

When a horn player is playing and you have a piano player, the first thing to do is accompany him and make him sound better. Sometimes you have a relationship where the horn player gives a lot of information to the piano player and the piano player tries to figure out what they are playing to make the harmony work. With Harold, you have some of that and you have a lot of him controlling the situation. I know from experience that a lot of musicians don’t like that. They are intimidated by it. On an aesthetic level some people like to be completely in charge of the improvisation. For me, I always felt that what he does to enhance the music is very valuable. So I always try to figure out what he is doing and get in there. I do feel that at this point I am one of the very few musicians that are close to him harmonically. Besides George Coleman of course! He’s a genius. I’m a student. But at this point, I don’t think that there are that many people that interact with him the way I do. And vice versa. So we enjoy playing with one another because he knows I can hear what he is playing. We can give each other musical cues just in one or two notes to change what’s happening.

In the early 1990s, you lived in Chicago for a while. In the early 1990s, you lived in Chicago for a while.

It was right after college and I wasn’t getting any work. My mother was living there and I had friends that had gotten out of university. Chicago still had a great scene at that time. And I knew a little bit about it. I knew something about the history of Chicago jazz and I knew that there were musicians that I wanted to see. It was a good alternative. I didn’t want to stay in New York. I didn’t feel that I was ready. I wanted to learn a lot more tunes and practice and work on my improvisational concept and sound. I moved back to New York in May 1992. I stayed in Chicago less than two years.

One of your early professional experiences was with Charles Earland. What did you learn from that experience?

Charles Earland was very enthusiastic and full of life. I played with him until the end of his life. He went through different periods. When I first started to work with him, he was still partying and towards the end of his life he was becoming a Baptist minister and we would pray before playing. Musically speaking, he was always the same. He was intense, had an incredible groove and always gave 100 %. He was very inspirational. We’d be playing the blues, playing for people instead of playing for musicians. A lot of young players grow up trying to impress their peers and outdo them in terms of technical things. You need to play with some kind of a connection with the people. We’re trying to communicate something to them. You have to be creative and make something out of material that might be mundane and not so complicated. Harold is that way too. While playing some hard jazz, he’ll throw in some boogaloo in the set.

In 1991, you came in second at the Monk Competition. How important was that event for you back then?

The year that I did it was the second year of the competition. Martin Krivin, who was the director of the jazz department at William Paterson, told me about it before I graduated. And Mabern encouraged me to try for it too. It was a big deal. Back then, if you thought you were a good player, you had to go through established channels to prove yourself at a big event like that or get signed with one of the major record labels and record your own album. It was a different era. You couldn’t just record your album and sell it on the internet. Now you can do that on your own and maybe make a hit.

How did your first album Straight Up come about? How did your first album Straight Up come about?

Bob Koester, the owner of Delmark Records, was based in Chicago and was always hinting around that he would record me. And after I moved back to New York, he finally decided to record me. For that record, I absolutely had to rely on Mabern for everything. I wasn’t ready to make a record! I had a couple of ideas for tunes but he came up with almost everything. That happened a few times. The last album we made, Touching, is a ballad record. I asked Mabern for untouched gems and he gave me a list a thirteen tunes! From Barbra Streisand to « Dinner for One Please, James » and « September of My Years »

Recently, you toured with Al Foster. How long did it take to connect with him musically?

I don’t think that I’ve ever played with a drummer like Al who’s both straight ahead, swinging, traditional and super modern. His concept of music is that it has to be different every time. Joe Chambers is kind of similar. Al has certain idiosyncratic tendencies that take a while to get used to. When something starts grooving, he has this way of putting the beat as far back as it could possibly go without slowing down. It’s a very strange feeling. Al is a great drummer!

You spend a lot of time on the road, in Europe and in Japan, when you are not playing in the US, and you record a lot both as a leader and as a sideman, how complementary is playing live and playing in the studio? You spend a lot of time on the road, in Europe and in Japan, when you are not playing in the US, and you record a lot both as a leader and as a sideman, how complementary is playing live and playing in the studio?

You know when you’re playing live, one song can be very different from another. In one song, you can feel great and the other terrible. You can never get too high or too low. Playing live is something that educates you about certain components of the music that you would never get if you were only in the studio. But vice versa, recording in the studio is very valuable. That’s where you get to find out what you sound like. It’s a learning experience because that’s where you can learn how to get the best sound that you can hit. For instance, now in the studio I play mezzo piano or mezzo forte at most. Joe Henderson would play pianissimo, super pianissimo. It’s better to have the sound engineer make the microphone more sensitive so you play more quietly and get a broader spectrum of sound. If you blow hard, at a certain point you get distortions and you can’t think. Recording is an art form in itself. Certain people are great in the studio. Some great players don’t do so well. For instance, Michael Brecker in his heyday in the 70s and 80s was a master of going in the studio and recording solos that were perfect. He knew how to do it and how to get his sound. Some people get very nervous in the studio. I am more nervous as a sideman than as a leader. As a sideman, any take could be the leader’s favorite…

Last March, Melvin Rhyne passed away. You recorded with him in the early 90s, 20 years after his last record date for Buddy Montgomery's This Rather Than That in 1969, when he reemerged in New York. What memories do you have of playing with him? Last March, Melvin Rhyne passed away. You recorded with him in the early 90s, 20 years after his last record date for Buddy Montgomery's This Rather Than That in 1969, when he reemerged in New York. What memories do you have of playing with him?

Melvin was an excellent player. He was swinging like crazy! He was probably more of a piano player than an organ player, that’s what he would tell people. He had some very slick tunes. They made so much sense and didn’t sound like anything else. He had a lot to offer.

*

Site : www.ericalexanderjazz.com

Discography

Leader/coleader

CD 1992. Straight Up, Delmark 461

CD 1992. New York Calling, Criss Cross 1077

CD 1994. Full Range, Criss Cross 1098

CD 1995. Eric Alexander in Europe, Criss Cross 1114

CD 1995. Up, Over & Out, Delmark 476

CD 1995. Stablemates, Delmark 488

CD 1996. Two of a Kind, Criss Cross 1133

CD 1998. Mode For Mabes, Delmark 500

CD 1998. Solid!, Milestone 9283 (coleaders John Hicks, Idris Muhammad, George Mraz)

CD 1999. Live at the Keynote, Video Arts 1144

CD 1999. Man With a Horn, Milestone 9293

CD 1999. Alexander the Great, HighNote 757013

CD 2000. The First Milestone, Milestone 9302

CD 2001. The Second Milestone, Milestone 9315

CD 2002. Summit Meeting, Milestone 9322

CD 2003. Heavy Hitters, Pony Canyon 30199

CD 2003. Nightlife in Tokyo, Fantasy/Milestone 9330

CD 2004. Dead Center, HighNote 7131

CD 2005. Sunday in New York, Venus 2042

CD 2005. The Battle, HighNote (coleader Vincent Herring)

CD 2005. Gentle Ballads, Venus 2020

CD 2006. Gentle Ballads II, Venus 2092

CD 2006. It's All in the Game, HighNote 7148

CD 2007. Temple of Olympic Zeus, HighNote 7172

CD 2007. My Favorite Things, Venus 3011

CD 2007. Gentle Ballads III, Venus 1011

CD 2008. Prime Time, HighNote 7201

CD 2008. Lazy Afternoon, Gentle Ballads IV, Venus 1027

CD 2009. Chim Chim Cheree, Venus 1038

CD 2008. Live at Marians, Bemsha Music 0902

CD 2009. Revival of the Fittest, HighNote 7205

CD 2011. Don't Follow the Crowd, HighNote 7220

CD 2011. Reeds and Deeds, Criss Cross 1332 (coleader Grant Stewart)

CD 2011. Gentle Ballades V, Venus 1054

CD 2012. Friendly Fire, HighNote 7232 (coleader Vincent Herring)

CD 2013. Touching, HighNote 7248

CD 2013. Blues at Midnight, Venus 1124

Coleader with One for All

Eric Alexander (ts), Jim Rotondi (tp), Steve Davis (tb), David Hazeltine (p), John Webber (b), Peter Washington (b), Joe Farnsworth (dm)

CD 1997. Too Soon to Tell, Sharp Nine 1006

CD 1998. Optimism, Sharp Nine 1010

CD 1999. Upward 1 Onward,Criss Cross 1172

CD 2000. The Long Haul, Criss Cross 1193

CD 2001. Live at Smoke: Vol. 1, Criss Cross 1211

CD 2001. The End of a Love Affair, Venus 2043

CD 2003. Wide Horizons, Criss Cross 1234

CD 2004. Blueslike, Criss Cross 1256

CD 2004. No Problem, Venus 35176

CD 2006. The Lineup, Sharp Nine 1037

CD 2006. Killer Joe, Venus 35351

CD 2007. What's Going On?, Venus 3022

CD 2009. Return of the Lineup, Sharp Nine 1042

CD 2010. Alexis Cole with One for All, You'd Be So Nice to Come Home To, Venus 1046

CD 2010. Incorrigible, Jazz Legacy 1001005

CD 2011. Invades Vancouver!, Cellar Live 91210

Sideman

CD 1991. Charles Earland, Unforgettable, Muse 5455

CD 1992. Charles Earland, I Ain't Jivin' I'm Jammin', Muse 5481

CD 1992. Randy Johnston, Jubilation, Muse 5495

CD 1993. Cecil Payne, Cerupa, Delmark 478

CD 1994. Randy Johnston, In-A-Chord, Muse 5512

CD 1995. Joe Magnarelli, Why Not 1104

CD 1995. Charles Earland, Ready'n'Able, Muse 5499

CD 1997. Steve Davis, The Jaunt, Criss Cross 1113

CD 1997. Cecil Payne, Scotch and Milk, Delmark 494

CD 1997. Melvin Rhyne, Stick to the Kick, Criss Cross 1137

CD 1997. Jim Rotondi, Introducing Jim Rotondi, Criss Cross 1128

CD 1997. Steve Davis, Dig Deep, Criss Cross 1136

CD 1997. Peter Bernstein, Brain Dance, Criss Cross 1130

CD 1997. Charles Earland, Blowing the Blues Away, HighNote 7010

CD 1998. Pat Martino, Stone Blue, Blue Note 53082

CD 1998. Sam Yahel, Searchin', Naxos Jazz, 86004

CD 1998. Jim Rotondi, Jim's Bop, Criss Cross 1156

CD 1999. Cecil Payne, Payne's Window, Delmark 509

CD 1999. Charles Earland, Cookin' with the Mighty Burner, HighNote 7014

CD 2000. Joe Farnsworth, Beautiful Friendship, Criss Cross 1166

CD 2000. Mike LeDonne, Then and Now, Double Time, 153

CD 2000. Freddy Cole, Merry-Go-Round, Telarc 83493

CD 2000. Jim Rotondi, Excursions, Criss Cross 1184

CD 2000. Melvin Rhyne, Classmasters, Criss Cross 1183

CD 2001. Ian Shaw, Soho Stories, Milestone 9316

CD 2001. Freddy Cole, Rio de Janeiro Blue, Telarc 83525

CD 2001. Harold Mabern, Kiss of Fire, Venus 2011

CD 2002. David Hazeltine, The Classic Trio Meets Eric Alexander, Sharp Nine 1023

CD 2002. Norman Simmons, Synthesis, Savant 2043

CD 2003. David Hazeltine, Manhattan Autumn, Sharp Nine 1026

CD 2003. Jimmy Cobb, Cobb's Groove, Universal 9334

CD 2003. Ian Shaw, A World Still Turning, 441 Records 20

CD 2004. Mike LeDonne, Smokin' Out Loud, Savant 2055

CD 2004. Jon Weber, Simple Complex, 2nd Century Jazz 5637348673

CD 2004. Joe Magnarelli, New York-Philly Junction, Criss Cross 1150

CD 2004. Joe Farnsworth, It's Prime Time, 441 Records 26

CD 2005. Freddy Cole, This Love of Mine, High Note 7140

CD 2005. Terry Gibbs, Feelin' Good, Mack Avenue 31022

CD 2006. Mike LeDonne, On Fire, Savant 2080

CD 2006. Grant Stewart, Estate, Videoarts Music 1282

CD 2007. David Hazeltine, The Inspirational Suite, Sharp Nine 1039

CD 2008. Larry Willis, The Offering, HighNote 7178

CD 2010. David Hazeltine, Inversions, Criss Cross 1326

CD 2010. Joe Chambers, Horace to Max, Savant 2107

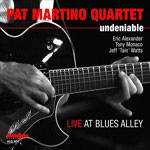

CD 2011. Pat Martino, Undeniable, HighNote 7231

CD 2012. Harold Mabern, Mr. Lucky, HighNote 7237

CD 2013. Jim Rotondi, Hard Hittin' at the Bird's Eye, Sharp Nine Records 1050

CD 2013. Champian Fulton, Sings and Swings, Sharp Nine 1049

CD 2013. Dee Daniels, State of the Art, Criss Cross 1362

Videos

Number Three : Eric Alexander (ts), John Swana (tp), Peter Bernstein (g), Kenny Barron (p), Peter Washington (b), Carl Allen (dm), extrait de l'album "Full Range" (2001)

Where or When : Eric Alexander (ts), Harold Mabern (p), Nat Reeves (b), Joe Farnsworth (dm), extrait de l'album "It's All In The Game" (2006)

How Are You? : One For All, Steve Davis (tb), Eric Alexander (ts), Jim Rotondi (tp), David Hazeltine (p), Peter Washington (b), Joe Farnsworth (dm), extrait de l'album "The End Of A Love Affair" (2008)

Big G : One For All, Eric Alexander (ts) Jim Rotondi (tp), Steve Davis (tb), David Hazeltine (p), John Webber (b), Joe Farnsworth (dm), extrait de l'album "Invades Vancouver!" (2010)

Cheese Cake : Harold Mabern (p), Eric Alexander (ts), Nat Reeves (b), Joe Farnsworth (dm), extrait de l'album "Kiss Of Fire" (2001)

Ritual Dance : Eric Alexander & Vincent Herring, Eric Alexander (ts), Vincent Herring (as), Mike LeDonne, John Webber, Carl Allen (dm), extrait de l'album "The Battle. Live At Smoke" (2005)

Blues For All : Jim Rotondi Quintet, Eric Alexander (ts), David Hazeltine (p), John Webber (b), Joe Farnsworth (dm), Smalls 2009

Amsterdam After Dark : Eric Alexander Quartet, Eric Alexander (ts), Grant Stewart (ts), David Wong (b), Philip Stewart (dm), Festival Internacional de Jazz de Punta del Este 2012, Uruguay

Edward Lee : Eric Alexander/Vincent Herring Quintet, Eric Alexander (ts), Vincent Herring (as), Harold Mabern (p), Joris Teepe (b), Joris Dudli (dm), Aneby Konserthall Sweden, 2012

*

|

|