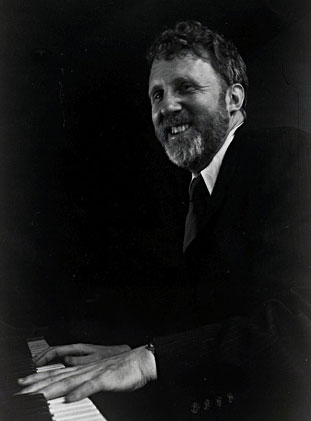

Ran Blake

Dr. Jazz and Mr. Blake

Ran

Blake is a pianist above suspicion. One might expect that of him. But

behind his kindness, his trimmed beard and his smiling eyes hides a

Boston strangler, a Dr. Mabuse, a Monsieur Verdoux or Arkadin, a Harry

Lime. Ran Blake is little like Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. He’s a

cinephile. In addition to his great musical knowledge, he has developped

through the years a personal repertoire of mental images which frame,

influence and exhiliration take its sources in film noir. Since 2004, he

hosts the Annual Halloween Film Noir Concert at New England

Conservatory of Music (NEC) in Boston with his colleague and friend,

trombonist Aaron Hartley, a theme night around a film noir where current

and former students, members of NEC and guests perform music to scenes

from selected films. For instance, the last events focused on « Laura »

in 2013 (based on scenes from Laura (1944) by Otto Preminger ; Leave her to Heaven (1945) by John M. Stahl ; Whirlpool (1949) by Otto Preminger), « Brando Noir » in 2012 – The Wild One (1953) by Laslo Benedek ; The Young Lions (1958) by Edward Dmytryk ; The Appaloosa (1966) by Sidney J. Furie ; The Night of the Following Day (1968)

by Hubert Cornfield and Richard Boone – and « Shadow of a Doubt » in

2011 – Shadow of a Doubt (1943) by Alfred Hitchcock ; Le Boucher (1970)

by Claude Chabrol. For each series, the participants, most of the time

Blake’s former students, are asked to use his method of placing the ear

at the center of musical development.

Ran Blake, born in 1935, has been teaching at NEC since 1967, invited by Gunther Schuller, president of the Conservatory from 1967 to 1977, who enhanced the position of jazz at NEC. Ten years earlier, Schuller coined the term « Third Stream » at a lecture at Brandeis University to identify the music that unites formal ideas inspired by classical and contemporary music (for instance, Stravinsky, Shostakovich, Messiaen) with jazz and improvisation. The two met in 1959 at Atlantic Records. Schuller invited him to study at the Lenox School of Jazz during the summers of 1959 and 1960. In 1973, Ran Blake created the Department of Third Stream Studies, renamed Contemporary Improvisation Department as the « Third Stream » soon explored more diverse musical sources. Ran Blake, born in 1935, has been teaching at NEC since 1967, invited by Gunther Schuller, president of the Conservatory from 1967 to 1977, who enhanced the position of jazz at NEC. Ten years earlier, Schuller coined the term « Third Stream » at a lecture at Brandeis University to identify the music that unites formal ideas inspired by classical and contemporary music (for instance, Stravinsky, Shostakovich, Messiaen) with jazz and improvisation. The two met in 1959 at Atlantic Records. Schuller invited him to study at the Lenox School of Jazz during the summers of 1959 and 1960. In 1973, Ran Blake created the Department of Third Stream Studies, renamed Contemporary Improvisation Department as the « Third Stream » soon explored more diverse musical sources.

As a sharp teacher, Blake is interested in developping the individual musicality of his students and has been researching a method to shape and nurture their personal style. The « Third Stream » is a state of mind at the service of pedagogy. It is not a musical genre. It all starts from this observation: western civilization has been dominated by the eye, and by the written, to a point that it rules our musical learning, governed by the eye and not the ear. With the exception of African and Asian cultures, orality has vanished. This observation, which seems like a common-sense approach, points out the methodological errors that were introduced centuries ago and that are today established as truths. Blake promotes an alternative: to teach music by ear, reconcile body and spirit in a more intuitive approach to develop listening and musical memory. Such is the purpose of Primacy of the ear, published in 2011, a 60-page essay complemented by ten appendices. In nine chapters, Ran Blake analyzes the key elements of this method: personal style, musical memory, listening, learning a melody, personality, building a personal repertoire and integrating it. In fact, he is the first one to use this method as a musician, a composer and a teacher. From 1986 to 2009, he taught summer school courses at NEC that focused on a specific musician and/or composer, resulting in months of preparation. We could cite as an example his courses on Thelonious Monk (1986), Stevie Wonder (1988), Sarah Vaughan (1994), Duke Ellington (1997), Ornette Coleman (2003), Dmitri Shostakovich (2006) and Louis Armstrong and Ella Fitzgerald (2009).

Interview by Mathieu Perez

Photos and documents by courtesy of New England Conservatory Archives

© Jazz Hot n°667, Spring 2014

Jazz Hot: Is The Primacy of the ear a method?

Ran Blake: It is a method and a philosophy book about music. It’s not a book about ear training but more about developping memory. There are also skill building tips. It’s practical for music critics and people who want to write about music as well because it improves your ability to hear.

Do you use this method yourself? How early did you start using it?

Yes, 90 % of the time I use this method. I had a teacher in Springfield, MA, and I noticed I could repeat what he was doing after listening to him a few times. I disliked the reading. I never codified this before I moved to Boston. People asked me how I got certain chords so I made an appendix. But it’s not the way I learned music. You can’t remember everything. You have to make your own gumbo. This method would be so much better if it were taught on a one-to-one basis to take into account the student’s personality.

What inspired this method? What didn’t you like about the way music was being taught?

Music was taught through sight. In the music, you mimic the teachers and watch their hands so that you can learn. I had some wonderful teachers but they wouldn’t take ten minutes at the end of the class to see what I had picked up. I would like them to play, that way I could repeat things that they had just played. It doesn’t mean that I played it correctly. I still think that written music is helpful if you can’t get a chord. There was no sense of memory back then. Now there is some of that in classical music where you remember things but it’s all through the eye. Of course if you’re a great musician, your eye looks at music and you hear it. Gunther Schuller can do that. Good conductors can do that. I had some great teachers but it all came from the intellect, the hand, the eye, and not from the heart. I found that that’s what was missing.

When did this method come about?

I joined the New England Conservatory of Music in 1967. I had a couple of students in New York. And by the second year, I realized that people needed written music with them every minute. I should say that my method is not always popular with the students. There should be an emphasis on developping your own style. And first, you have to listen to history and understand other musicians and composers. I think there would be room for also looking at scores for some more conventional teaching. That’s why I love to talk to teachers and other people in education where we can blend things. A drummer starting out should review Max Roach’s solos, maybe in the Freedom Now Suite. He may have to develop more technique and then combine it with my approach to help him shape his own style. I believe in this more than in my own music.

How early were you certain about this method?

By 1969 I knew. I had been a student of Gunther Schuller. His eyes hear everything. Within six months, I realized that this is the way to study.

The Primacy of the ear puts the ear at the center of musical learning. Does that mean that we have been focusing on the wrong thing?

I think so. For myself, I never focus on the written. You don’t study Picasso through your ears. Music is the only artform that is taught by another sense, perception.

How does putting the ear at the center influence your physical experience?

I’m not the only improviser that uses ears! Thousands do! I’m not always focused on the rhythm section. I love the singers. My choice of focus will be the human voice and the orchestral colors. My visual sense comes through movies. But I don’t dictate to my students what to see. Breathing is also very important. I can't stress it enough. Furthermore it’s not about pure memorization like the violinists that use the Suzuki technique to learn a Chopin étude. I want musicians to breath.

You define a « recomposition » as creating something new based upon original structure.

Loads of people do that! For the Gershwin album, I first got to know all the songs by ear. I also had some transcripts. Ella Fitzegrald did an album, Chris Connor did one, Monk too, so I knew the pieces and could play them conventionally. Then I would go back to the original artist and just listen away from the keyboard. And I would dream about it. Why did Chris Connor decide to do « The Man I Love » as an upbeat number? What was going through Monk’s mind? And I would fantasize plots you could find in films by Hitchcock and Chabrol. Sometimes my own world can submerge me. Now dealing with Ricky Ford and Sara Serpa for instance, I don't focus solely on my own fantasies.

Three essentials themes are musical memory, working before playing on the piano and build a custom made repertoire.

Up until recently, I would practice some musical ear exercises in the morning. That made me improvise on pieces to awaken the ear. I have a course called music aerobics. It’s like the yoga of the ear. My repertoire is not perfect for my students. Sometimes I have them listen to music so that I can convey the things that they are not hearing. Building a repertoire is a wonderful way of amassing history. Once they widened their taste, they have to pick what is best for them.

« Improvisation is like storytelling. » What do you mean by that?

In the old days before tv, my grandparents would tell stories and there would be variations. My father told a story about a woman who would come occasionally. She didn’t have much money so she would do some cleaning or stop by and cook food. My father’s father would ask her for help to fix things. And she never could hear. Then one day he asked her to marry him. And she said : « Oh yes, Monsieur. » In one version, my grandfather’s wife is still alive and comes in and gets angry at both of them. In another one, there was something else going on. The story would vary. But there is still a frame. There is an art of storytelling. I like Billy Strayhorn’s « Lush Life » because it has many meanings. I think of an old landlady that I lived with and I remember playing this tune in her house in New York. She was 89 in 1960. Once she showed me her music box and began to sift through momentos from her childhood. Everytime I play « Lush Life », I have this lady in mind. One story leads to another. It’s hard to always have a story. It takes practice. There should be more than chord changes to a standard. I think about adding fantasy to reality the way a painter would mix his paints. It either comes or not. You can’t think of being original every minute. And sometimes it’s great just to play with history and read something you can recompose and be simple.

You talk about the art of listening. Listening is difficult and requires discipline.

Students are very eager. They want to get out and around. They have parents that are worried if they are going to make a living. Some people come to school and already have a CD out privately. Listening takes time and you need to keep refreshing. For young people it’s hard to forget yourself. Music is not like reading a Dickens book. Put on an hour of Chet Baker. Pick your favorite pieces. Hear them. Maybe three or four times a month. You don’t need a specific schedule. It’s just time for Chet. The more you hear it, you more you’ll know which note comes next. It will be in you. It does take a lot of time to listen and explore music. And you need to revisit those interests. There is a limit to what can be held. Students have five courses, begin dating, live with new roommates, hang out, practice, etc. I don’t think they have enough patience. Memorizing music is hard. It takes years of developping.

You define a « liquid composition » as the relation between improvisation and composition. And you add that an improvisation should unfold spontaneously.

Let’s say Sarah Serpa and I are doing a 3-4 minute extended improvisation on a Billy Wilder film. Then when one goes through the experiences of memorizing. Maybe the liquid composition we did is little too challenging so we’ll do it a little easier. So besides the original melody we have something else and we have two different railroads. This is only an aspect of a liquid composition. There are many more. I feel that would have been interesting for Sarah Vaughan because of her range precision. She could have handled a few more challenges.

*

Contact : http://ranblake.com/

Discographie

Leader/Coleader Leader/Coleader

LP 1962. The Newest Sound Around, RCA Victor LSP-2500

LP 1966. Ran Blake Plays Solo Piano, ESP 1011

LP 1969. Blue Potato & Other Outrages, Milestone Records, HBS 6084

LP 1976. Breakthru, Improvising Artists Inc. 373842

LP 1976. Wende, Owl Records 05

LP 1977. Crystal Trip, Horo Records HZ 06

LP 1977. Open City, Horo Records HDP 07-08

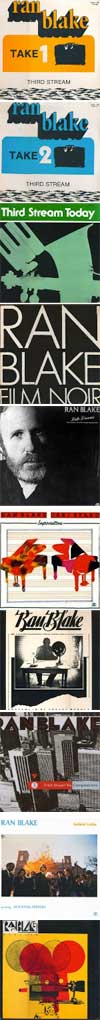

LP 1978. Take One, Golden Crest 4176

LP 1978. Take Two, Golden Crest 4177

LP 1978. Realization of a Dream, Owl Records 012

LP 1978. Rapport, Novus AN 3006

LP 1978. Film Noir, Novus AN 3019

LP 1979. Third Stream Today, Golden Crest NEC 116

LP 1981. Duke Dreams, Soul Note 121027

LP 1982. Improvisations, Soul Note 121022 (avec Jaki Byard)

LP 1982. Third Stream Re-Compositions, Owl Records 017

LP 1982. Portfolio of Dr. Mabuse, Owl Records 022

LP 1984. Suffield Gothic, Soul Note 121077

LP 1985. Vertigo, Owl Records 041

LP 1986. The Short Life of Barbara Monk, Soul Note 121127

LP 1987. Painted Rhythms: The Compleat Vol. 1, GM Recordings 3007

LP 1988. Painted Rhythms: The Compleat Vol. 2, GM Recordings 3008

CD 1989. You Stepped Out of a Cloud, Owl Records 789212 (avec Jeanne Lee)

CD 1991. That Certain Feeling, hatART 6077

CD 1992. Epistrophy, Soul Note 121177

CD 1994. Roundabout, Music & Arts 4807 (avec Christine Correa)

CD 1994. Masters From Different Worlds, Mapleshade 1732 (avec Clifford Jordan)

CD 1997. Unmarked Van, Soul Note 121227 CD 1997. Unmarked Van, Soul Note 121227

CD 1997. A Memory of Vienna, hatOLOGY 505 (avec Anthony Braxton)

CD 1999. Something to Live For, hatOLOGY 527

CD 1999. Duo En Noir, Between The Lines 004 (avec Enrico Rava)

CD 2000. Horace Is Blue, hatOLOGY 550

CD 2001. Sonic Temples, GM Recordings 3046

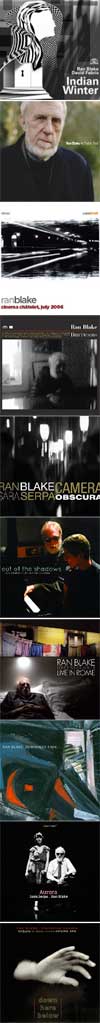

CD 2005. David Fabris, Indian Winter, Soul Note 121327

CD 2006. All This Is Tied, Tompkins Square 1965

CD 2008. Cinéma Châtelet, Sans Bruit 001

CD 2009. Driftwoods, Tompkins Square 1966

CD 2010. Out of the Shadows, Red Piano Records 14599-4404-2 (avec Christine Correa)

CD 2010. Camera Obscura, Inner Circle Music 015 (avec Sara Serpa)

CD 2011. Grey December, Tompkins Square 2592

CD 2011. Whirlpool, Jazz Project 3002 (avec Dominique Eade)

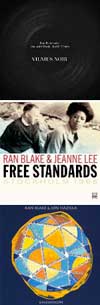

CD 2012. Vilnius Noir, NoBusiness Records 45 (David Fabris)

CD 2012. Down Here Below, Red Piano Records 14599-4411-2 (avec Christine Correa)

CD 2012. Aurora, Clean Feed 264 (avec Sara Serpa)

CD 2013. Free Standards-Stockholm 1966, Fresh Sounds 791 (avec Jeanne Lee)

CD 2013. Kaleidoscope, CIMP Records 391 (avec Jon Hazilla)

Sideman

LP 1960. Annette Stevens, Marvelous Industries 01202

LP 1966. Patty Waters, College Tour, ESP-Disk' 1055

LP 1982. The Fringe, Hey, Open Up!, Ap Gu Ga 003

LP 1988. Claire Ritter, In Between, Zoning 1001

CD 1989. Franz Koglmann, Orte Der Geometrie, Hat Art 6018

CD 1991. Eleni Odoni, Mistral, Zoning 1003

CD 2001. Claire Ritter, River of Joy, Zoning 1007

CD 2001. Plexus, Plexus, Mother West 0057 CD 2001. Plexus, Plexus, Mother West 0057

CD 2003. Windmill Saxophone Quartet, A Touch of Evil, Mapleshade 9432

Videos

2001 Improvisation par Ran Blake

2010 Somewhere over the Rainbow

2012 Mahler Noir composition sur différents événements de la vie de Mahler

2012 Ran Blake ; Life in Music 2012 (image de Ran Blake Jeanne Lee)

2010 Ran Blake et Sara Serpa Lisbonne 19 décembre 2010

2013 Ran Blake : A life in Music Documentaire

Ran Blake. Above the Sadness. Trailer Bande annonce d'un documentaire ; Interview

Ran Blake : Pepper

*

|

|