Jazz Foundation of America

Don’t You Know We Care?

Jazz musicians have given a lot to the world. But the world hasn't always given back to them. Although they worked all their lives at clubs, in recording sessions, many, whether they are great leaders or lesser-known sidemen, struggle to survive. Some have savings; others have family support or other benefactors. Most are without pension.

Many reasons explain this situation. With the development of the record industry, of jazz clubs, the work of the musicians, especially sidemen, hasn’t found fair acknowledgement and compensation. Often paid in cash and unaware of a pension fund jazz many musicians found themselves without any social protection. However, there is a union. It’s called the American Federation of Musicians 1, founded in 1896, and it is linked to the American Federation of Musicians and Employers’ Pension Fund 2, created in 1959. It took years before the union organized jazz musicians and activist musicians to increase awareness among the African-American musicians about their rights. Because the pension fund "was kept a closely guarded secret”, as Jimmy Owens 3 puts it, as its existence was communicated only to white musicians.

We all know the tragic lives of many musical geniuses that made the great history of jazz. We tend to forget the contributions on a daily basis or on a more local scale of so many diverse and talented artists. These stories were published in the issues of Jazz Hot from 1935 to 1940. Correspondents who hung out in Harlem and other cities across the US depicted the constant struggle among jazz musicians to survive. If the situation has improved in terms of rights, the living conditions of the elderly, the access to health care and social aid are tremendously lacking. The Jazz Foundation of America (JFA) was founded upon this need.

In 1989, a group of jazz lovers gathered to defend and promote jazz as a patrimony. Its founding members were Herb Storfer 4, a businessman and board member of the New York Jazz Museum, Phoebe Jacobs, vice president of the Louis Armstrong Educational Foundation, Cy Blank, a businessman, singer Ann Ruckert and pianist Dr. Billy Taylor 5. Shortly after, JFA took a decisive turn to reorient their approach towards social issues. Activist musicians Jimmy Owens, who cofounded the Collective Black Artists in 1969, Jamil Nasser and Vishnu Wood, convinced the founding members to help and support the elderly musicians that were living in precarious conditions. Over the years, JFA has developed thanks to the support of philanthropists, notably Jarrett Lilien, former president of E-Trade, now president of JFA, and Agnes Varis, philanthropist who financed an action plan in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina in 2005.

Each year, JFA organizes two fund raising events, the "Great Night in Harlem”, in May, and the "Jazz Loft Party”, in October. The organization doesn’t receive any public funding and functions on a national and international level. The identity of the beneficiaries remain anonymous except when they accept to become spokespersons, like Clark Terry, Cecil Payne, Odetta, Freddie Hubbard…

In 1992, JFA became an emergency fund. Priorities orient their actions and the support they provide has evolved with the needs of the community over the years. Satisfying Dizzy Gillespie’s last wishes, the Englewood Hospital, in New Jersey, agreed to provide free care to musicians. So many cannot afford medical attention they haven't seen a doctor in years.

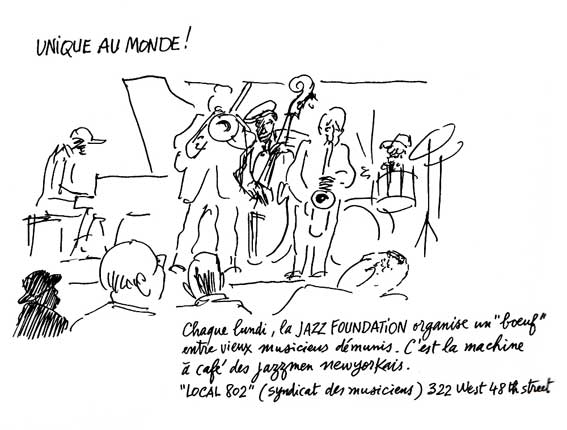

The photos used were taken during the Monday Jam Sessions 6. In this interview, Wendy Oxenhorn, Executive Director of JFA since 2000, and Alisa Hafkin, Director of Social Services, describe the activities of this invaluable foundation linked to so many touching stories.

Interview by Mathieu Perez

Drawing by Cabu, from Cabu New York, Courtesy of Les Arènes

Photos by Jon Hammond, Sánta István Csaba, Mathieu Perez and the Jazz Foundation of America, by courtesy

(The credit and the caption are displayed when you hover your mouse over the image.)

Thanks to Gina Reder, coordinator of the Monday Jam Session, Cabu, Jon Hammond, Sánta István Csaba

© Jazz Hot #668, Summer 2014

Jazz Hot : How did the Jazz Foundation of America (JFA) get started?

Wendy Oxenhorn: It was started by Herb Storfer in 1989. He must have been in his 70s at that time. He had a headhunting business and out of his home in Manhattan he would help musicians to promote jazz. Billy Taylor, Ann Ruckert, Phoebe Jacobs and Cy Blank were part of it too. With Vishnu Wood, Jimmy Owens and Jamil Nasser, the JFA became an emergency fund because musicians from all over needed help.

What was Dizzy Gillespie’s contribution to JFA?

W. O. : Dizzy Gillespie had asked the Englewood Hospital 7 if they could help the musicians the way they helped him. When he died in 1993, Jimmy Owens did a beautiful tribute to Dizzy called « 100 trumpets for Dizzy » in Englewood. After that, the hospital agreed to help medically for free. But before that, Herb was paying for everything from his pocket. The Englewood Hospital has since donated $5 million in free care. The average is about $400,000 a year. They have treated over a thousand musicians. Dr. Frank Forte has never turned a musician down that didn’t have insurance.

How quickly did JFA expand?

W. O. : When I got there in 2000, they had a little office at the Local 802 Musicians Union building. I would write the checks, interview the musicians to see what was going on, do the paperwork, etc. In two months, we went from helping 35 musicians to 70. At the end of the first year, we helped 150 musicians as the word started to get around. When I realized who the musicians were that we were helping not to get evicted, I couldn’t believe it. At that time, I knew a lot about blues but not that much about jazz. So I rented the movie A Great Day in Harlem by Jean Bach. That’s how the « Great Night in Harlem » event at The Apollo began. An event to increase awareness and raise funds. It happened in eight weeks. We gathered 100 musicians. Everybody showed up. You name it they came. We raised $350,000. It was amazing.

Before, how would JFA raise money?

W. O. : Before that, JFA would organize a little party at Herb’s place and raise something like $20,000. But when I came, they hadn’t raised any money in three years. There was $7000 left in the bank.

Was it easy to convince people to donate money for older musicians?

W. O. : When you do something wonderful to really help people and you do what you say you do, the money just comes. If you forget yourself to help the others, the universe gives you what you need to continue.

Who calls first?

Alisa Hafkin : Most of the time the person in need. We are very respectful. When friends call, the first question that I ask is: « Does that person know you are calling? ». Jazz musicians are very proud. Reaching out for help is very challenging. So when I call, it’s better that they know that someone had called on their behalf so that they don’t feel ashamed. And if I am reaching out to them, I’ll let them know very clearly that I am the one calling and they have the choice.

What is the process?

A. H. : We have a process of intake. We try to focus our attention on jazz and blues musicians over 50. In some cases age isn't relevant. One is if it’s a medical emergency. Then age is not an issue. The other is if musicians are supporting children under 18 in their home. So a 45-year old musician with an 8-year old and a 3-year old is someone we are going to help. If there is a situation that involves a child, the child becomes the priority. We have to make sure that the children are safe and have a roof over their heads. So first we find out what is going on. Then we identify their music history. We ask the musicians for a bio, a list of CDs, write-ups, venues they played in, all external sources. We deal with people that were diagnosed with cancer, kicked out of the house because of domestic violence, musicians whose tour was cancelled, who broke a finger, found out that their music was on YouTube or being sold on iTunes, others that are very depressed, etc. Sometimes we need to get other organizations involved because the situation requires more financial help over a longer period of time. Depending on the situation, we have to assess if it’s an immediate crisis or not. Once we have stopped the bleeding, we have to see if the person can sustain himself. If it’s an elderly person who can’t gig anymore and pay his rent, we cover the rent for him and continue to provide support. Maybe he could get a roommate or relocate, have food stamps, get in touch with his family. We try very hard to engage the families if there is a family. Jazz musicians lived on their own for so many years. Often when they are older, family just isn’t around. We become their family and always look out for them.

How many people do you help?

A. H. : When I first started in 2005, we would help two or three people a day. Today it averages 30 a day. Not every case is an emergency. On August 23rd, 2005, Hurricane Katrina hit. The calls exploded. 70 people would call a day. We have maintained a very strong relationship with musicians in New Orleans. Many were displaced to other states. Part of our work was to help them move back and reinvigorate the music scene.

W. O. : We help a little under a thousand individuals, maybe a little more. It depends on the year. The way we put it is 5000 case assists per year, which means 5000 times we have come to for help. It can be one person two times. Say someone comes to us for back pains. We send him to the Englewood Hospital. It turns out he has stage 4 cancer. Immediately he has to cancel the gig. So we pay the rent for a few months. Now we are dealing with housing and medical issues. That’s two cases for that person. Once we have heard of a great old musician that is blind and alone but has never asked for help. He needed someone to do his laundry and provide him with food as he can no longer take care of himself. At that point, that musician was living on M&M’s and liquid protein diets. Cecil Payne was living this way! So first we got him food delivered to his house. Then an assistant came in to help him with function. We put him in our jazz in the schools program and he began to perform again. His whole life changed. That would have been three cases.

Was it easy to convince people to get help at first?

W. O. : These are people that have worked hard their whole lives and always supported themselves. Some were single parents who would never have considered asking for help. Musicians have always lived on very little, rather it was during the depression or the recession, but they live their own way. So for them to ask for help is a big deal. Usually I have to hear from someone else. Now we have developed such a beautiful relationship in the community that people know about us and come to us. At the beginning, it was very hard to convince them. So many musicians, even the most famous one, have been touched. Even if they are still making big money in gigs, say their wife died, they have no one handling their affairs, they are old, dementia is setting in and no one wants to bring it up because they are revered. It happened with a very famous musician. Every two days, I had to make sure that the dog was fed or that a cigarette wasn’t still lit somewhere in the house. It’s a very tricky situation. How can you say to someone that they should no longer be living alone? In one case, I convinced a musician to have a roommate, we found someone he knew. But when he was admitted into the hospital, the doctors wouldn’t let him go back home. We did not let him down. We would all go and visit him. There are so many great things you can do when you visit someone at the hospital. Playing music is one of them.

Some musicians helped by JFA accept to become spokespersons. One of them is Clark Terry.

W. O. : It’s so hard to believe. Someone like Clark Terry was on the Johnny Carson Show! 8 You would think he would have royalties. He is going through so much medical trouble. When you are old and infirm, you can’t make the gigs you used to. We have musicians in their 90s that are still touring. But depending on your health, you can’t always do that. He has had his second leg amputated. We were able to help Clark Terry by paying for a health aid to come to his home three days a week. We also pay for oxygen to be delivered to him.

How did the idea of performing in nursing homes begin?

W. O. : There was a great musician in a nursing home. The family wouldn’t let him have visitors. Everybody was very worried. It turned out the musician was in terrible pain and was suffering from some kind of dementia. It would have been very cruel to him to have visitors. So I organized with a bunch of his old friends a visit to his nursing home to play music for the residents, knowing that he was there. He cried when he saw his friends. There are so many beautiful miracles you can do for people and doesn’t cost anything.

What is the situation of older uninsured musicians?

W. O. : Most of them have not been to doctors in 20 to 40 years. When you don’t have insurance, you don’t go for the big tests. Many of the musicians that could have lived another 10 or 15 years discovered that they had stage 4 cancer and it was too late. Every year we do a little benefit for the Englewood Hospital at Jazz at Lincoln Center that raises $15,000. And they give free cancer screenings. The Englewood Hospital never turned down a musician.

How did the Emergency Housing Fund start?

W. O. : The need created the solution. We go to court with people who are about to be evicted from the apartment they have lived in for 30 years. The landlord wants them out because he can increase the rent to $2500-3000 a month when they are only getting $700. One time, someone came to me regarding a musician who was about to be evicted. His name was Jimmy Norman. He was one of the Coasters. He was also Bob Marley’s first producer. He wrote some of the songs with him and never got a dime. The most famous song he wrote is « Time Is My Side », which made the Rolling Stones famous in America. I went to the courthouse with him. The landlord was there and wanted him out. Jimmy owed him $2500. I went to his attorney and asked him if he had any idea who Jimmy Norman was. It turns out he loved Bob Marley and the Rolling Stones. This was at the beginning of my job. I didn’t know anything about the law. So I asked this attorney for advice. Not only did he become an advisor to JFA but he made it so that the landlord erased the $2500 that he owed. Then we cleaned up Jimmy’s apartment because of his bypass surgery he couldn’t lift a thing. He hadn’t cleaned his apartment in years. When we cleaned it up, one of our volunteers found a cassette of him playing music with Bob Marley. Nobody had ever heard what was on that cassette. Another volunteer got Christie’s to auction it off. After the commission, Jimmy got $18,000. He paid his rent for one year. Then he bought a computer and an audio editing suite. He created his own version of « Time Is On My Side » and recorded other songs. Judy Collins put his record, Little Pieces, on her Wildflower label. The man was on his way to a second life. He had this one gig at Roth’s Steakhouse and he lived for this gig. When the restaurant closed, he died within months. He died for the first time in November 2011. I say for the first time because each time we went to the hospital, the doctors would say this is the end. They told me he was going to live six months and he lived 11 years. He had 16 lives, more than a cat.

Does JFA have a housing facility?

W. O. : We don’t. It’s a big wish. To have a place where the musicians could retire and live very cheaply. It could be in New York or outside of the USA, like in a hotel that no one is using anymore in Montreux.

What is the Agnes Varis Jazz 9 in the Schools program?

W. O. : The best thing we have ever done is our Jazz in the Schools program. We started this after 9/11 when the musicians had their gigs cancelled and no one was touring. We gave money to the musicians to go and perform at inner city schools. Now we do it in 19 states. The musicians that settled in other states after Katrina and 200 musicians in New Orleans still are making a little money playing in the schools. They keep the music alive. In New York, we have over a 100 musicians that are doing this. This is the future for us. People don’t have the money to go and hear live music. Live music is a dying artform. Now you have your iPhone, iPod, iPad, you listen to music by yourself and you miss the whole point. Music is a healing. A concert is a beautiful shared experience. Go to concerts! The little clubs don’t pay much and you can’t support yourself anymore the way the musicians used to. Now everyone needs a day job. A true musician practices six hours a day and then plays ’til 3 in the morning and goes to after hours places to play in jams. You lived in the music. Now it’s very difficult. You don’t live in the music like that anymore. Rents are high. Everyone is struggling and suffering. It’s affecting the world not to have music makers. In our own little way, we are contributing somehow to keep the music and the musicians alive.

More than any other organization, JFA really reaches out to the musicians and cares for them.

W. O. : Musicians have given so much to the world. It's not like they didn't do anything for anybody and expected to be helped. They worked six, seven nights a week their whole lives. They were there for us. When we got married, we danced to their music. When we were sad, they got us to over heartbreak. I can’t tell you how many times Abbey Lincoln and Chet Baker saved my life by listening to their music. What else gives you that sense of hope? How could we let them go down in their old age?

A. H. : We’ll call and say hello. When it’s 103 degrees, we’ll call and ask if their air conditioner is working. If not, we’ll run up at the hardware store and get them an air conditioner. Or if it’s really cold, we’ll ask if they have enough heat. If not, we’ll bring a heater. I don’t know anybody that does that. There’s a lot of reaching out and a lot of follow up. A man last year had done a lot of work on cruise ships. The money was good when he worked a lot. He would be covered for the year. He developed a bad pancreatic issue and had to go through gallbladder surgery the night he was supposed to go on his cruise. Then he developed an infection for two months so he couldn’t work. He was behind on his rent for four months. We gave him a month’s rent. Another organization gave him another month’s rent. Then we referred him to a city organization for the one-shot deal. If someone is in trouble, the city will help if you have resources from other organizations and if you can prove you can cover your rent afterwards. During that time, we called him to know what had happened with the one-shot deal, if he got the check from the other organization, if he had the court date and needed us to go along with him, etc. We reach out in order to avoid emergencies. This man is old and doesn’t know the system. So we’re not going to leave him go through this all alone. A. H. : We’ll call and say hello. When it’s 103 degrees, we’ll call and ask if their air conditioner is working. If not, we’ll run up at the hardware store and get them an air conditioner. Or if it’s really cold, we’ll ask if they have enough heat. If not, we’ll bring a heater. I don’t know anybody that does that. There’s a lot of reaching out and a lot of follow up. A man last year had done a lot of work on cruise ships. The money was good when he worked a lot. He would be covered for the year. He developed a bad pancreatic issue and had to go through gallbladder surgery the night he was supposed to go on his cruise. Then he developed an infection for two months so he couldn’t work. He was behind on his rent for four months. We gave him a month’s rent. Another organization gave him another month’s rent. Then we referred him to a city organization for the one-shot deal. If someone is in trouble, the city will help if you have resources from other organizations and if you can prove you can cover your rent afterwards. During that time, we called him to know what had happened with the one-shot deal, if he got the check from the other organization, if he had the court date and needed us to go along with him, etc. We reach out in order to avoid emergencies. This man is old and doesn’t know the system. So we’re not going to leave him go through this all alone.

How much did 9/11 and Hurricane Katrina change the scene in New York and New Orleans?

W. O. : It completely changed the whole music scene. For months nobody was going out. The club and the restaurant owners had no business and couldn’t pay the musicians. Musicians agreed to work for free until the business came back. They would pass the basket. And the club and the restaurant owners got used to not paying them even when business started to come back. All of a sudden, students from jazz schools whose parents are providing for them or people that have day jobs could afford playing off the basket. This changed the music scene. You went from the veterans to the inexperienced who can get by but who are not masters yet. It changed the quality of the music that people heard. After Katrina, one organization started giving money to the clubs to pay the musicians. That was a mistake. Again, musicians began playing mostly for the basket. Club owners get used to not paying the musicians, whose pay is very little anyway. This subject is heartbreaking. But we have to look passed that. The 2008 economic crisis created such devastation in people’s pockets. Now they can’t go out anyway or as much. People stay home. Clubs are having a harder time surviving. 9/11 was the beginning of this and the economic crisis was the end.

How soon after Hurricane Katrina did JFA launch the Jazz in the Schools program in New Orleans?

A. H. : Within two weeks, Wendy came up with this idea to help musicians who had lost everything. Some musicians ended up in Mississippi, Kansas, Alabama, Las Vegas, Houston, wherever, with nothing. We found the funding to pay for musicians to perform in schools and nursing homes. This program now exists in 19 states. It was a way to help musicians get refocused on playing music. It has also helped people in the hospitals and nursing homes. I can’t tell you the stories we hear of kids in hospitals that are catatonic, absolutely shut down. The musicians would say they saw them bopping their foot or an old person in a nursing home trying to get out of his chair because he was so moved. That is priceless. We need to keep broadening this program. It’s such a positive experience.

JFA was very active when Hurricane Sandy hit in 2012. Could you describe your action at that time?

A. H. : Hurricane Sandy hit on October 22nd, 2012. It paralyzed the lower half of New York and Brooklyn, New Jersey, Long Island. We went into our database to collect a list of musicians that lived in Lower Manhattan. It could only be in Lower Manhattan because we had no way of reaching musicians in Brooklyn and New Jersey. There’s a supermarket a block away from our office and we scoured it for any type of non-perishable food we could find. We bought water, long underwear, flashlights, gloves, batteries and half-chickens. Our assistant director Joe Petrucelli drove in from Brooklyn, because there were no subways, so we basically trudged downtown for days with all of our supplies. We could not call anyone or ring a doorbell. All electrical systems were down. Once you got below 42nd Street, it was a dead zone. We spent days going downtown yelling into windows hoping that someone would come out of the building and let us in to go and knock on the door of a musician. When people saw us at their doorstep, they would just cry. They couldn’t believe it. One guy walked uptown because he wanted to eat something hot. He wanted a roast chicken and couldn’t find anything so he bought a sandwich. Then he walked back. It was a long walk for him. He was like on East 3rd Street. And when he got home, here we were. He was blown away. We gave him supplies that would last. This particular guy was not in our database because we had never helped him before. Somebody else told us about him.

Many musicians lost everything.

The stories that emerged were horrifying. There was a group of musicians who had a rehearsal space at Westbeth, in West Village, that was completely flooded. They had stored their instruments there. One guy kept their sheet music from the 1600s. It had been destroyed. What those musicians lost could never be brought back. We’ve tried to help them getting new instruments so that they can work again. Many lost their homes too. Another gentleman spent 20 years as a photographer chronicling jazz musicians and was preparing a book. He had his work stored at a friend’s place in the East Village. He never heard from the friend so he assumed everything was ok. Six weeks after the storm, he discovered that all of his negatives had been under water and were molding. He is now trying to separate the negatives and save whatever he can.

Contact Jazz Foundation of America : jazzfoundation.org

1. American Federation of Musicians, www.afm.org

2. American Federation of Musicians and Employers’ Pension Fund : www.afm-epf.org

3. In 1996, Jimmy Owens, Bob Cranshaw, Benny Powell, Jamil Nasser created the Jazz Advisory Committee to raise awareness among musicians about their rights and to encourage them to contribute to the pension fund.

4. Herbert Storfer (1924-2007) was a businessman, a jazz lover and a philanthropist. Parallel to running businesses, Storfer cofounded the non-profit Doing Art Together with his wife Muriel and served as a member of the board of the New York Jazz Museum. He cofounded the Jazz Foundation of America in 1989.

5. Billy Taylor (1921-2010)

6. Concerning some of the musicians that were at jam session that evening: Zeke Mullins (p ), played with Lionel Hampton for 20 years ; Bob Cunningham (b), cousin of Bobby Few (p), played with Ahmad Jamal in the 1950s, Dizzy, Freddie Hubbard, etc. ; Billy Kaye (dm) played with Thelonious Monk, Stanley Turrentine, Frank Strozier, Illinois Jacquet, etc. ; Art Baron played with Duke Ellington, Sam Rivers, John Tchicai, Joey DeFrancesco, Bobby Watson, Elliott Sharp, Frank Wess, Louie Bellson, etc. ; Fred Staton, 99 years old, the brother of Dakota Staton (1930-2007), who went to school with Billy Strayhorn, is a non-professional saxophonist (he worked in the food industry), is a member of the Harlem Blues & Jazz Band.

7. Englewood Hospital

8. From 1962 to 1994, Johnny Carson was the host of the Tonight Show. When he was hired, he increased the budget of the Tonight Show Band, led by Skitch Henderson. In 1966, Henderson was replaced by Milton DeLugg (1966-1967), then by Doc Severinsen (1967-1992). Over the years, members of the Tonight Show Band included Snooky Young (tp), Ernie Watts (sax, fl), Branford Marsalis (ts), Lew Tabackin (ts, fl), Bucky Pizzarelli (g), Shelly Manne (dm), Ed Shaughnessy (dm), Louie Bellson (dm), to name a few. Clark Terry stayed in the Band from 1962 to 1972

9. Agnes Varis (1930–2011) was the founder and president of AgVar Chemicals Inc. and Aegis Pharmaceuticals as well as a philanthropist. She became involved with JFA in 2004. In 2005, she made a $1 million grant to expand the Jazz in the Schools program and to provide help to New Orleans musicians displaced by Hurricane Katrina.

*

|

|